PART ONE: PRELIMINARY CONSIDERATIONS

1. Theological Inquiry and Hermeneutics

"Are you the King of the Jews?" (Jn 18:33). This is a decisive question Pilate posed to Jesus. By this question, John allows his readers to begin an inquiry about the identity of Jesus (1) . Every question arises from a state of mind with which the questioner directs his investigation. The question of Pilate is not only used by John as a means to furnish some historical information about Jesus, but is intended to be a perennial question of John's readers to Jesus as well.

To the question(s) of Pilate, the Johnannine Christ (2) does not only give an answer but corrects also his way of questioning and requires the questioner(s) to "see" with the eyes of faith. This is exactly what Jesus did in the Trial and John just repeats it in his own way. From the first question of Pilate (18:33) to the seventh: "Where are you from? " (19:9), John has skillfully shown that Jesus managed to shift Pilate's earth-bound mental state to a superior level. Pilate is no longer interested in his Galilean origin, for at that moment he perceives Christ to be something more that a human mortal. His augmented "fear" (19:8) and "solicitude" to release Jesus (19:12) confirm this. The Trial projects a series of solemn and progressive proclamations of Jesus' identity and at the same time is blended with a crescendo of urgency for decision (belief or disbelief). In an ironic yet theologically correct (3) way, he is called "the King of the Jews" (18:39; 19:3), "the Man" (19:5) and "God's Son" (19:7). In the same way John wants to lead his readers into this christological horizon (4) where they will have to face Christ face to face. In fact, a careful reader may realize that as those actors involved in the drama of Jesus' life have to come to a decision (belief or disbelief) in his signs and words, so the reader himself should do the same. This is the very intention stated at the end of the Fourth Gospel (20:30-31), where John addresses his readers (5).

Today when we read this paragraph again, we want to grasp John's theological message so as to enter into the christological horizon he intended to bring forth. Our inquiry will be: Who is this Christ who manifests himself in the Johannine description of the Trial? This is a theological inquiry based on the conviction that Christ still speaks to us through John's Gospel. Thus our essay is mainly a theological one, though it only helps to "see" an answer without pretending to be exhaustive.

At this point, hermeneutics must be called into play. It is a complicated issue that lends itself to endless discussion, for it is concerned with theology, philosophy, history, linguistics, sociology, psychology, cultural anthropology and so on. The text (of the Trial) projects a meaning of its own, but at the same time. is open to an infinity of interpretations beyond the intention of the author (6).

However, from the theological point of view. hermeneutics can be considered a service of the word and of the confession of faith. It attempts to bring out the transcendence of the word. which is simply the transcendence of speaking human subjects in relation to their conditionings (7) . Any transcendence presupposes a "breach" and a "leap" over which faith must be involved as pre-comprehension. Thus it should be worked out within the living reality of the Church, which is the recipient of the Divine revelation ("Ecclesia discens") prior to all differentiation of the offices in the hierarchy. Her primary activity preserves with fidelity and docility the revelation which has been given to her in "words and signs'' (8) and still resounds in the present day (9) . For this the Holy Spirit endows different charisms on the Church, and, in particular, on the Apostles and their successors, that in "receiving" and "handing-down" the Divine Truth they may never fall into the wrong path. The interpretation of a scriptural text should help to map out a route that makes possible a common journey for those who want to encounter God (10).

Of course the entire process of the transmission of the Deposit of Faith should not be limited to the moments of infallible canonization of Holy Scripture or proclamation of dogmas; it is, above all, to be "lived" in the worship (11) in which God's glory will dwell upon men. "Homo vivens Gloria Dei". As a matter of fact, every Good Friday when we listen to the "Passio" according to John. we sense that Christ still speaks of himself to men (especially in the Liturgy) through John's writing.

The "Trial" itself was already a route theologically mapped out by John that led his contemporary to Christ. However, the mapping may be blurred by the long distance of time and cultural differences. The "letter" may no longer be a sufficient guide to the "spirit" (12). Through a hermeneutic process, we thus wish to recover its "sufficiency" so that the "Trial" may appear again as an ever renewed route to the threshold of the Mystery for the modem men.

Our working area is the text itself. We do not employ an exegetical process like Text Criticism, Literary Criticism, Form Criticism, Redaction Criticism (13) and. so on. All these stages of work are presupposed. By adopting a philologico-semantical analysis, I try to furnish a "hermeneutical space"°–a field of possibilities for play in which any man may immerse himself both receptively and actively as a creative perceiver of meanings; for "play" is a mode of receptive-active encountering realities from which meanings of life can be derived (14). Such a hermeneutical space results from an existential interaction between the text to be interpreted and the interpreter who has the conviction that the more he reads the text, the more it becomes telling. The repeated readings should go hand in hand with the analysis of verbs, vocabulary, syntagmas, syntax, textual and contextual structures and so on. Any intelligent reading may lend itself to an interpretation but here it is the philologicosemantical analysis, without excluding other methods and approaches, that throws light upon our readings.

Futhermore, the outcome of a hermeneutic space is based on the mutual relationship between the "event" and "writing". By event here we mean the historical Trial itself. The writing, refers not only to a simple production of text. but above all to that special text so designed (and so inspired) as to provoke faith within the readers (15) . The Trial happened in the past but has a permanent force appealing to men of different times and places. The writing is to save it from forgetfulness, and hermeneutics is to keep it perpetually "alive" to those who seek to step over the threshold of the Mystery.

2. The Johannine Theology of History

A careful reader of the Trial will notice that John continously mixed the present tense with the past. He adopts the inceptive use to give a striking effect of continuation°–something is happening. John is not only reporting the past in a lively way by using the historical present, but also on the theological level, he is showing us the presence of the Mystery that appeals, here and not. to his readers. In order to understand John's subtlety, it is expedient to dwell at some length on his theology of history.

The conclusion of John's Gospel (20:30-31) reveals two major interests, namely, the Revelation through the events of Christ, and their salvific implications for men who are appealed to make a decision of faith either in the acceptance or refusal of his Revelation.

Now Jesus did many other signs (semeia) in the presence of the disciples, which are not written in this book; but these are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God. and that believing you may have life in his name" (20:30-31).

For John the "semeia" are the events of Christ themselves, the sight of signs should lead people to believe in him (cf 1:51; 2:11, 23; 3:2; 4:48, 54; 6:2, 30; 7:31; 9:16. 23 and so on) and his revelation. Now this dominant theme determines also John's conception of time.

The coming of Christ is the irruption of the eternal into the temporal sphere.

"The Word became (aorist) flesh and dwelt (aorist) among us" (1:14).

"For the judgment, j came (aorist) into this world" (9:39).

The use of the aorist indicates subtly the inception of the state in a global sensed that the dwelling and coming of God took place at a certain point of time in the past and has thus inaugurated the New Era of God's Presence in human history. The idea of the irruption of the eternal into the temporal leads us to a conception reminiscent of the kairos of the vision of Paul. All the events take place in the stream of single moments (chronos) one after another. With the coming of Christ, there has come true the fullness of the chronos (Gal 4;4). In the unrolling of the plan of God (oikonomia), there has arrived the climax°–the Christ-event in relation to which every event is to be defined as "before" or "after".

"Formerly you were without Christ, strangers to the covenants of the promise" (Eph 2:12).

Now he (Christ) has reconciled you in his body of flesh" (Col 1.22) (17).

However John has skillfully focalized this idea of kairos into the hora of Christ (18).

"Truly, truly I say to you the hour (hora) is coming and now is (nun estin)" (Jn 5:25).

The hour is the full accomplishment and unfolding of the Divine Plan, that is, the glorification: Cross and Resurrection-the returning to the Father and the sending of the Holy Spirit. The accent of the time, therefore, is on the present nun estin. The past and future with reference to chronos are brought together in the "hour" of Christ and they become a unity in the believers (20:31: pisteuontes). The future will bring nothing decisively new. for the eschatological accomplishment no longer takes place in the future at the end of time but right now in the Christ event.

The eschatological hour further supercedes the dichotomy between the past and future insofar as it appeals to man, here and now, who has to decide to accept or to refuse Christ's revelation. That is why Jesus came for judgment (5:22: krisis and 9:39 krima) upon the world - a division between the believers and unbelievers. Thus life and death, light and darkness appear together. The hour is the moment of judgment pregnant with salvation and decisiveness in the present. The hour is no longer a time between times, but is the definite consummation in which one has no need to wait for any end of the historical yet to come. For it is now all consummated (19:30: tetelestai). For the first time. the traditional dualism of the aeons (the present historical time and the future accomplishment at the end of time) derived from the Jewish apocalyptic is now eliminated. The coming of the logos subsumes the entire human "procursus" in the historical time. Instead there is another dualism, expressed by Hellenistic categories, between light and darkness, truth and falsity, believers and world, that which is above and that which is below (19).

In short, the Johannine theology of history is based on the presence of the eternal Word in the temporal world. This presence constitutes the Christ event, the Final Establishment, the Last Word of God towards mankind. Thus the Christ event becomes a contemporizing of eschaton. Salvation history subsumes human history and transforms it into a new creation. Whatever takes place in the world is to be judged with reference to the krisis in Christ.

Thereby the historicity of man comes to expression, namely, that man through faith in Christ moves from decision to decision. In the very decision of faith, man takes his Christie shape or becomes unbeliever. It results in the tension between the light and darkness and constitutes the real drama of eschatological existence°–already and not yet°–in human history:

"The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it (...)

but to all who received him, who believe in his name, he gave power to become children of God" (1:5,12).

However the force that overcomes this tension is Agap6. the Father loves the world by giving the Son (cf 3:16), and the Son loves the disciples with the love which the Father exhibits towards Him (cf 13:1; 15:9) in order that they may love one another (cf 13:34) and that the world may believe that is was the Father's love (cf 17:21; 14:31) for which the Son comes to the world. The love of God. consists not in loving him but in being loved by him, and whosoever is loved by God also loves others (cf 1 Jn 4:7-21). Hence loving others becomes the acceptance of God's love and, at the same time, the unifying force of the light that dissipates the darkness (20).

Granted that John has a theological conception of history which is foreign to empiricopositivistic historiography, it does not follow that the hisotricity of the trial is totally at stake. Some authors, like P. Winter, hold that "from John 18:29 onwards the Fourth Gospel contains nothing of any value for the assessment of historical facts''(21). The statement is wildly sweeping and ungrounded. "While there is evidence of some degree of elaboration by the author, the most probable conclusion is that in substance it represents an independent strain of tradition, which must have been formed in a period much nearer the events than the period when the Fourth Gospel was written, and in some respects seems to be better informed than the tradition behind the synoptics, whose confused accounts it clarifies" (22).

Hence it can be said that there are two perspectives in John's account of the Trial. One is historical: another we could call eschatological. Though they are of two different domains they are both nevertheless real.

2.1. The Historical Perspective of the Trial

By the standard of modem historical certainty, Jesus' Trial and Death on the Cross can be regarded as an assured "nuclear fact". However the history of Jesus that led him to the crucifixion was, above all. a theological one. To qualify it as "theological" is not to slight the authenticity of the fact; on the contrary it furnishes a point of contact between the empirical world (of facts) and the Mystery (of faith). With all this blending of fact and faith, John's account of the Trial is still the most consistent and intelligible that we have ever possessed. Only John makes it clear why Jesus was brought to Pilate. He was accused as an evildoer (cf 18:30) and should be condemned to death. Then he was considered, or at least, insinuated as testes (cf 18:40). This is a term that can refer to a simple robber, a rebel, or even more probably to a Zealot who makes armed conflict against the Roman rule (23).It is nor a simple political offence but a serious rebellion against the Pax Romana (24) which is rooted in a political religion, namely, Caesar is the god and thus requires everyone to offer due obedience to him. The Romans could not bear such a rebellion, or better the Kingship of Jesus, which would endanger the authority of their political god (25). Although John makes it clear from the mouth of Pilate that Jesus was not guilty of this charge (3 times: 18:38; 19:4, 6). he was still condemned on this charge (cf 19:15-16, 20-22).

The portrait of Pilate yielding to the subtle interplay of political forces carries a certain conviction, as John intends to show, that Jesus was reckoned with transgressors of the Jewish Law and was condemned as a blasphemer:

"We have a law and by that law he ought to die, because he made himself the Son of God" (19:7; cf Lev 24:16) (26).

This is also in common with the tradition of the Synoptics.

Furthermore John's chronology, where the judicial process takes place on the 14th of Nissan, is more credible than that of the Synoptics, where it takes place on the feast of Passover (27). Though it is difficult to separate the historical kernel in a modern sense from the account of a theological history, yet it would also be too hasty to draw the conclusion that John has tried, at any cost, to jam all the facts into a theological frame in such a way that no trace may be founded in history. If modern historiography is foreign to John's intention, then we have no reason to search for it. For the truth narrated by John is not deprived of historicity, but is chiefly concerned with the interiorization of faith, openness to transcendence and a spiritual journey towards the self-unfolding Mystery.

2.2 The Eschatological Perspective of the Trial

In the fourth Gospel, it is the "Glory" of the Son that determines the content of the Trial. The whole NT unanimously agrees that the Resurrection was the climax of the Glory of the Son, for it was the mighty act of God par excellence. For John however, this "Glory" had already been visible during the ministry (28). The Glory is the irruption of the eternal into the temporal, and thus the anticipation of the Eschaton. What was supposed to happen at the end of time has now happened to Jesus, who is to unroll the salvific plan of God°–the Final Establishment. It all starts with incarnation:

"The Word became flesh and dwelt among us.

full of grace (charis = hesed)

and of truth (aletheia =' emet)

we have beheld his glory (doxa = kabod), glory as of the Only Son from the Father" (1:14).

The Glory of the Son is. thus. the Word (logos) spelt out by God to all men that His Mercy (hesed) and Fidelity ('emet) have now come true. That is why. for John, in the great "hour"°–in which the Trial took place°–Jesus is not only a simple man who by the envy of the Jews was accused as evildoer, rebel and blasphemer, but the One who has to come to exercise the eschatological function (29). In spite of the ironic setting, Jesus in the Trial is presented solemnly as the King, the Final Revealer, the Universal Judge, the Eternal Light, the Incarnate Truth, the Visible Glory, the Lamb who takes away the sins of the world (......) and brings forth salvation for those who believe in him.

3. The Development of the Narratives of the Paschal Event

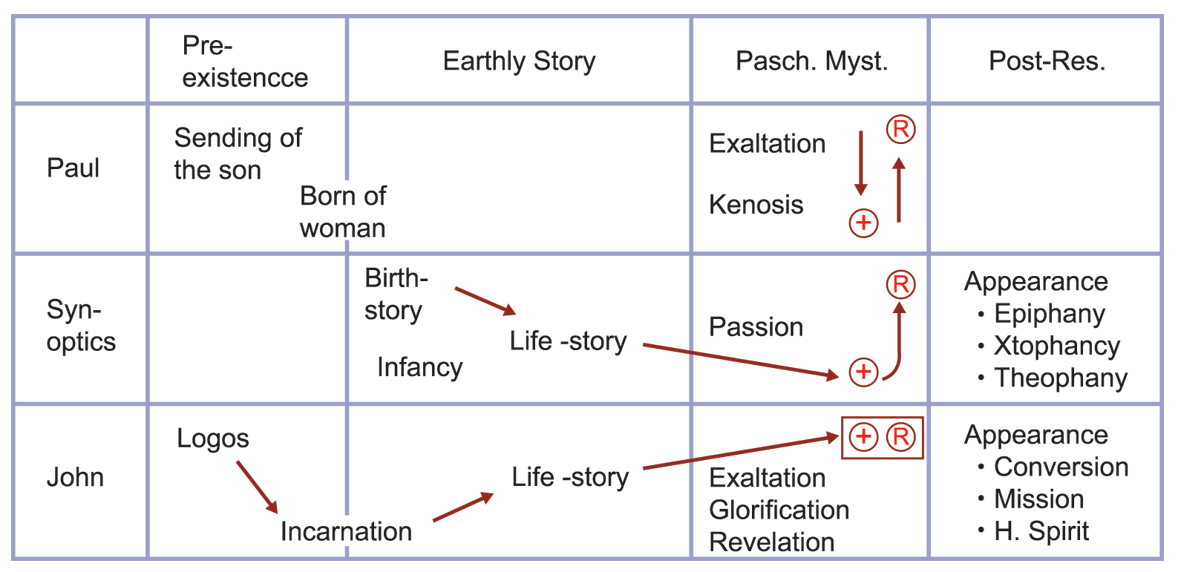

In John, historical instances are always gilded with theology so much so that Death and Resurrection°–two historical instances°–form one single Paschal event. In fact in different stages of preaching, the NT writers became more and more aware of this fact. Three stages can be distinguished here.

First, in the early preaching of the Apostles, especially that of St. Paul, we may notice that the Cross and Resurrection had created in the early witnesses two distinct experiences. At first, they were totally disheartened by the scandal of Jesus' Cross, but then were over whelmed with joy at the encounter with the Risen Lord. It is the apparition experience that makes the first witnesses recognize the identity of Jesus as the Son of God sent forth by the Father, born of woman (...) (cf Gal 4:4f), who. being found in human form, humbled himself and became obedient unto death, even death on the Cross: therefore God has highly exalted him (cf Phil 2:8-9). These two contrasting movements, katabasis (descending ) and anabasis (ascending), though they are of the same pre-existent Son of God, are in some way due to the two sharply contrasted experiences of the early witnesses.

In the second stage of the preaching, there emerges also the life-story of Jesus and, at the end of it, the appearance narratives. This does not mean that the preaching Church had now invented new material; rather, always remaining faithful to the earlier traditions, it adopted a new form of preaching for some particular reason. In these narratives. Jesus was presented, right at the announcemnet of Messiah's birth, as the One from above, the Son of the highest; but then there followed the movement of kenosis until the point of death on the Cross. However, it will be an empty Cross°–a Cross that projects a light to the Resurrection by the confession of faith of a pagan centurion. This link between the Cross and Resurrection was further explained in the post-resurrection appearances by Christ himself. Hence at this stage, the Cross and Resurrection have been further unified as one single event.

In the third stage, John makes it even clearer that the Glorification takes place right away in the Exaltation of the Son of Man. The use of the verb hypsoo shows exactly the exaltation of the Glory and of the Cross. For John the katabasis movement takes place at the moment of Incarnation, and during the life-time of Jesus the anabasis movement goes upwards until the exaltation on the Cross. Note that in this upward movement, there is a crescendo of the revelation of the incarnate logos and a crescendo of disbelief that lifted him up on the Cross. What is on man's side the katabasis and humiliation, is the anabasis and glorification on God's side. John has marvellously unified these two contrasting movements at the moment of the "hour" where one can hardly disjoin the Cross from the Resurrection. They are of one single paschal Mystery.

Schematically, we can present the development this way:

"While the basic story remains fhe same. it (the Fourth Gospel) has been beautifully rewritten to present the Crucified Jesus as the consummate revelation of God's love (cf 13:1; 12:13; 19:30), lifted up from the earth in a final victory over evil (3:13-14; 8:28; 12:32), drawing all men to himself (12:20-12; 19:25-27) so that they may gaze upon the pierced one (19:37). It is here that God's work (ergon) is brought to fulfillment (see the use of telos and related verbs in 4:34; 12:1; 17:4; 19:29-30)"(30).

The trial for John was not only an important stage historically precedent to the Crucifixion of Christ, but should also highlight theologically the consummate revelation of God's love that invites man to a personal appropriation.

"In the New Testament it is above all St. John who emphasizes this aspect: truth is not simply the revelation which Christ brought by manifesting himself; under the action of the Spirit human beings must also appropriate this truth for themselves. In the Johannine writings 'to do the truth' (poiein ten aletheian) (Jn 3:21; 1Jn 1:6) means precisely to make the truth of Jesus one's own, so as thereby to reach the light" (31).

If John's word speaks about God and invites his readers to a confession of faith, then it is of interest here to elucidate the theological message contained in the trial of Christ described by John.